Herbert Schneider assumed leadership of the Hannes Schneider Ski School at Mount Cranmore following the April 1955 death of his father. Hannes’ passing was completely unexpected, and when it came he had been fully engaged with planning for the new East Slope and chairlift at Cranmore, and had just returned from a trip to New York to meet daughter Herta and son-in-law Karl Fahrner on their arrival from St. Anton.

On his last day of life, Hannes dictated several letters to Herbert, who took them down in shorthand, then complained of pain in his elbows and stomach. In those pre-EMS days it took time to arrange for an ambulance to the hospital, and Hannes died before its arrival. At his funeral in North Conway, skiers from across the country and abroad mingled with the local people who had become his friend.

At the time that Herbert Schneider took over the ski school at Cranmore, it was a busy and profitable concern. Hannes Schneider had virtually invented the ski school structure, and his fame in the skiing universe had attracted many patrons to North Conway. The ski school saw growth in every year between the arrival of the Schneiders in 1939 and 1955. There was a day when 800 lessons were taught at the mountain, and to give 200 lessons on a midweek day was unremarkable. Learning to ski on the long wooden skis and soft leather boots of the day required more practice and persistence than on today’s efficient ski equipment, and many returned to lessons week after week, for years at a time.

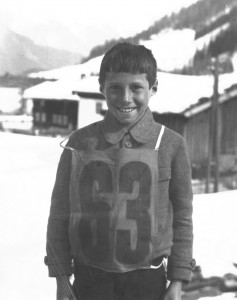

Herbert’s new role as Director of the ski school was one for which he had been prepared almost from birth. At age 11, he was sent to school at Feldkirch, about 40 kilometers west of St. Anton, to a Jesuit school named Stella Matutina. Here he played hockey and ran track after classes.

When he was older, he spent one year in L’ecole Superior de Commerce in Neuchatl, Switzerland, in order to polish his French skills. Hannes’s ski school in St. Anton was becoming increasingly cosmopolitan, and the ability to speak languages other than German was becoming important. Herbert expected to follow his formal education with a few years teaching skiing at Sun Valley to learn English, but events in Europe intervened.

When the Anschluss came in March 1938, Herbert and his sister Herta, also in school in Switzerland, knew little of the events in St. Anton. Hannes, from the beginning unimpressed at the rise of National Socialism in Austria, progressed to a firm refusal to treat with the Nazis from Innsbruck who gained influence in St. Anton. When the day came that Germany annexed Austria, Hannes was awakened at 3 AM and taken into custody along with four others, including the brother of Otto Tschol, who would live in North Conway and teach at Cranmore. One of those arresting Hannes sheepishly apologized for the way it was done, only to be fired for his solicitousness a few days later.

While Hannes was held in custody, first in the jail in Landeck then under house arrest in Garmisch-Partenkirchen Germany, Herbert and Herta stayed in Switzerland with sympathetic families.

The house where Hannes Schneider was held under house arrest in Garmisch, seen in 2012. Photo by Heide Allen.

All through the summer and fall of 1938 Hannes’s future was unknown. He was offered the directorship of the ski school in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, though the offer was withdrawn after pressure. Hannes’ wife Ludwina’s strong feeling was that if they could not resume their previous life in St. Anton, it was best to move as far away as they could.

This became a real possibility late in the year, as Cranmore’s Harvey Dow Gibson, alerted to the situation by Benno Rybizka, set his sights on having Hannes relocate to North Conway and operate the Hannes Schneider Ski School from Mount Cranmore. Gibson’s financial and political connections made this improbable scenario a reality in early 1939, and the arrangement had great appeal to Hannes and Ludwina because it allowed the entire family to leave Europe altogether, at a time that turned out to be on the eve of all-encompassing war.

Upon landing in North Conway, Herbert had two immediate obstacles to a career in ski instruction: he did not speak English, and he had never taught a ski lesson. The language barrier came down within 4 or 6 weeks, Herbert recalls, helped by intensive attendance at the North Conway theater watching Hollywood’s offerings with the other Austrian instructors in town—Toni Matt, Franz Koessler, Otto Tschol, and Benno Rybizka. Herbert spent his days shadowing the experienced instructors; he recalls Toni Matt as an especially gifted teacher of skiing. It was a time when technique was progressing so rapidly in Austria that Benno, who had been in America since 1936 and was unaware of the evolution of technique in Austria, criticized Herbert and Franz for making pure parallel turns without showcasing the stem phase of the turn.

It was only when he arrived in America that Herbert realized the extent of his father’s influence on the sport of skiing, as Hannes was not accustomed to speak of his role at home. Hannes, Herta and Herbert were made to feel at home in North Conway immediately, and soon gained wide acquaintance. However, the welcome release from European tension was darkened by the death of Ludwina Schneider shortly after the family’s arrival.

In his second year in North Conway, the 1939-1940 ski season, Herbert had his first class on his own. His first pupils were Mr. and Mrs. C.V. Starr, he being the insurance magnate who would soon come to dominate the ski area at Mt. Mansfield, and would finance the installation of a chairlift in St. Anton after the war. Herbert received his instructor’s certification in 1940, along with Toni Matt in an exam given by Roger Langley on the old Whiteface Trail in New York. It was on that trip that he received his nickname “Zip”, invented by Walter Maguire, who drove them to the event.

The advent of war in Europe in 1939, and America’s involvement dating to the Pearl Harbor attack changed everything for Herbert’s generation on both sides of the Atlantic. Herbert, Toni Matt, and Otto Tschol joined the newly formed 10th Light Division (Alpine) training at Camp Hale, Colorado in August 1943. They were sent directly to Camp Hale, bypassing basic training. On their arrival there Toni and Herbert were assigned to the 10th Recon, the unit containing the better skiers and climbers that were detailed to teach skiing, climbing, and winter survival to the main division. Lacking basic training, Herbert and Toni were assigned to individualized training with Sergeant Nelson Bennett, a Lancaster NH native.

In the winter of 1944, Herbert was on detached duty to the Upper Peninsula of Michigan and Wisconsin, training troops of the 76th Division in winter warfare. He returned to Camp Hale in time for the division’s move to Camp Swift in Texas June 1944; just before his departure he became a US citizen in Eagle, Colorado.

The 10th, now designated the 10th Mountain Division, spent the winter and spring of 1945 in fierce combat in the Apennine Mountains of Italy. Herbert was with the 86th regiment during this period, winning a Bronze Star for quick thinking when he and a group from his I & R platoon encountered a German patrol in a minefield behind enemy lines.

At the end of the war, the Herbert’s unit found itself in Riva, near the north end of Lake Garda, a place where Herbert’s mother Ludwina had worked before her marriage. It was also close to the point where Hannes’ unit had ended the First World War. In the months between the German surrender in Italy and the 10th’s return to America, Herbert and two others were sent to Innsbruck to retrieve some German mountain equipment. The proximity to St. Anton made a detour irresistible, and Herbert found himself welcomed at the home he had left years earlier. A celebration ensued when word of Herbert’s return got around, and bottles of wine that had been hidden for the duration were brought out.

The Sporthaus Schneider, the combination ski shop, guest house and Schneider family home, remained in the possession of the family through the war years thanks to lease arrangements made on behalf of the family by Karl Rösen, the man with whom Hannes had found refuge in Garmisch-Partenkirchen after his 1938 arrest. Rösen, not a Nazi himself, seems to have had connections at the highest levels of the Nazi party dating from decades earlier. He was also a skiing friend of Hannes’ and his interventions to get Hannes out of Austria and to secure the ownership of the St. Anton property surely eased the Schneider family’s troubles greatly. During the war years, the house was leased by Rudi Matt, one of Hannes’ senior instructors, and became a rest and recreation center where German military personnel learned to ski.

The brief, happy return of Herbert to St. Anton was overshadowed by the tragedy that just ended. Many young men of Herbert’s generation never returned from the military. Herbert’s best friend as a boy, Pepi Jennewein was one. A champion ski racer, he was recruited as a fighter pilot by the Luftwaftte, as were other ski competitors for their competitive impulses and rapid reflexes. Jennewein became a fighter ace, recording many kills, before being shot down. Another St. Anton skier, Pepi Gabl, was present and saw a parachute open, but Pepi Jennewin’s fate was unknown for decades. In recent years it was learned that he survived in a Russian POW camp until the early 1950s.

A civilian once more in the fall of 1945, Herbert returned to North Conway and Cranmore, helping Hannes operate the ski school and the mountain. Business at the mountain grew as skiing regained its prewar popularity. Cranmore was in an excellent position to capitalize on skier interest because not many ski resorts existed before the war, and the great postwar boom in ski area construction was yet to come.

Ownership of Mount Cranmore devolved to Mrs. Harvey Gibson after her husband died in 1950, and it was she who selected Herbert to lead the ski school in 1955. A few years later, in 1963, when her financial advisers thought it best for her to sell the resort, Mrs. Gibson vetoed their plan to sell to a group of Cranmore managers and made it possible for Herbert to assemble a small group of investors and purchase the mountain. Herbert remained the on-site manager throughout his ownership tenure.

As a ski area owner, Herbert became active in industry groups like Eastern Ski Area Operators and the New Hampshire Ski Area Operators. He went onto the Board of the Professional Ski Instructors of America in its second year, and remained a Board member and officer for years.

In February 1966 Herbert married Doris Beaudet of Connecticut, a Northeast Airlines stewardess who was based out of Boston. Herbert and Herta had been on a flight with Doris, who soon thereafter came to Cranmore for a ski school lesson. Herbert remembered her name from the nameplate that airline crews then displayed on the cockpit door during their flights, and they struck up a romance. After their marriage, their first son Hannes was born in 1967, and his brother Christoph was born a year later.

As the son of the pioneer developer of ski instruction, Herbert Schneider was literally the second generation of businessmen making a living from skiing. Rapid developments in skiing had changed the ski business landscape since the heyday of Hannes’ ski school in the 1930s. First and foremost, just as Hannes was encountering his political problems in St. Anton, mechanical ski lifts were becoming widespread. Once it became obvious that lifts would become an integral part of skiing, the ski schools that had evolved when the only uphill capacity was measured in lung power had to adjust and incorporate lifts into the teaching scheme. Ski lifts allowed more time for downhill, hence more experience for each day on the slopes. Skis and ski boots became more refined. Both developments had the effect of reducing the time a novice had to spend in ski lessons. The Schneiders and other European instructors found Americans to be vastly less patient than Europeans, and had to make allowances for that attitude.

Just as years of ski lessons became less critical for a newcomer to gain skill on skis, a great surge in construction of ski resorts got underway in the northeastern US. Existing ski resorts like Cranmore quite suddenly had to cope with vastly increased competition from new areas on the higher peaks of the northeastern mountains, and from European and western destinations made newly accessible by air travel. Herbert struggled with these trends, and engineered the gradual expansion of lifts and terrain. He continued Cranmore’s early lead in mechanical snow grooming, and arranged for the installation of snowmaking around 1969 or 1970. While Cranmore lost the pre-eminent position in the hierarchy of eastern resorts it held in the 1940s, it remained a viable mid-sized ski area with a loyal following. In 1984, faced with the unwillingness of his partners to invest more in the resort, Herbert put the mountain up for sale and bowed out of the ski business.

It was 45 years after Herbert and Hannes took their first run on Cranmore. On the way down they had paused, and Hannes told Herbert, “Well Herbert, it isn’t St. Anton, it isn’t the Arlberg, but we’re going to love it here”.