By Bettina Hoerlin

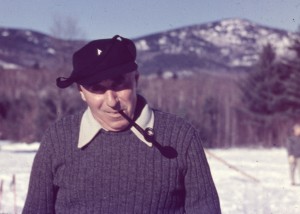

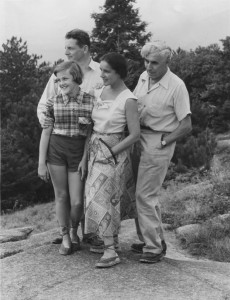

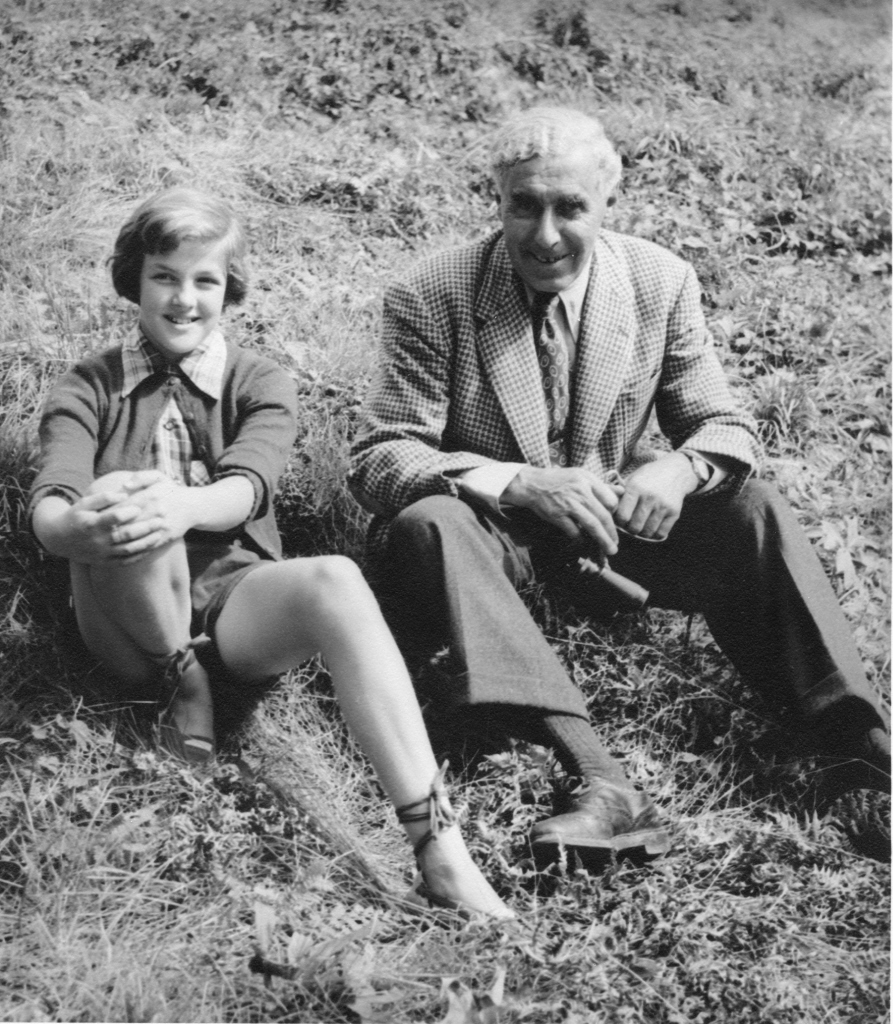

It seemed like it would never end: up, up, and up, one step behind the other, my stride mimicking the slow and steady “Bergsteiger” (mountain climber) pace set by the two tall men in front of me. One was my father, who had once held the world record for having climbed the highest mountain ever summitted and the other, my godfather, better known as the father of modern skiing. Hermann Hoerlin and Hannes Schneider, friends from the “old” country (respectively Germany and Austria), had both fled fascism and forged new lives in the United States. On a beautiful autumn day in 1951 they were leading me up Mount Washington, the first mountain I had ever ascended. I was 12 years old and knew of my father’s impressive feats: first ascents in the Alps, the Himalayas and the Andes during a time when international climbing enthusiasts competed for glory and recognition. And I knew about my godfather’s famous reputation: the Skimeister who had formalized the so-called Arlberg technique, popularizing skiing and giving it panache by teaching royalty, actors and actresses, and industrial and financial moguls around the globe.

Father and godfather were formidable company for a neophyte and a nervous one at that. We had gotten up early in the morning and Hannes’ daughter Herta had prepared breakfast while my mother packed our lunch. This was going to be a big day for me: a real mountain, an ascent of approximately 4,000 feet, and two intrepid guides. Before we reached the Headwall of Tuckerman Ravine, I was faltering but Hannes’ dramatic narration of Toni Matt’s famous schussing of the bowl in 1939 proved inspirational. The thought of an 85-mile per hour descent on skis made the steepness of the ascent by foot feel both more significant and more palatable. I gamely kept going, with encouragement from both Hannes and my father. But disappointment lay ahead. We were almost at the top when the sounds of cars and voices reached my ears. No one had mentioned there was a road to the top, much less a cog railroad. Instead of (relatively) solitary triumph and glorious quietude, I was amidst the multitudes admiring the view from New Hampshire’s tallest peak surrounded by the brilliant fall foliage of the White Mountains.

In my memory, that was the only time that I was upset with my godfather. I felt I should have been forewarned. Whether Hannes purposely did not tell me about Mt. Washington’s easy accessibility or whether he assumed I was aware of it, I’ll never know. No doubt it would have diminished my motivation to get to the summit. But all was quickly forgiven, especially since during the round-trip hike I was treated to hearing some remarkable stories about a long-standing friendship that started on one continent and continued on another.

Hannes and my father Hermann had met ski touring in the Alps in the late 1920’s. Younger than Hannes by ten years, my father had been described by a prominent British mountaineer as “… one of Germany’s most enterprising young mountaineers” with “…as brilliant a record of climbs as any young mountaineers in Europe.” [i] Many of his first ascents had been around Mount Blanc, Europe’s highest mountain, a huge massif with Aiguilles, sharp needle-like spires of harrowing rock, more difficult to scale than the mountain itself. [ii] Ascending them in winter was even more daring, but that is exactly what my father did, breaking all summer records for speed and establishing himself as a premier winter climber. Using a novel approach to alpinism at the time, he combined skiing and mountaineering, first donning skis to traverse across deeply crevassed glaciers and ice fields and then trading them in for crampons to ascend the sheer faces of the Aiguilles.

His unofficial consultant on all matters that had to do with skis and skiing was his friend Hannes. When in 1930, my father was asked to join an international expedition to the Himalayas, which planned to use skis to help achieve its goal of reaching the top of the world’s third highest mountain, he again turned his friend Hannes for advice. The expedition was not successful in their conquest of Kanchenjunga, but nonetheless bagged the highest peak (Jongsong, 24,482 feet) that had yet been summitted. In the course of the expedition, the team scaled a total of four peaks over 7,000 meters (22,966 feet); at the time only eight peaks over 7,000 meters in the world had been conquered. In utilizing skis during expedition, the high altitude record for skiing was undoubtedly set as well. Observed one of the climbers, “ Balancing at low levels is automatic, but (between 21,000 and 22,000 feet) a conscious effort is required, whilst a swing is distinctly hard work.” [iii] Bending ‘zee’ knees for well-executed stem Christies undoubtedly had unique challenges as did the unpredictable terrain of glaciers and crevasses. Reportedly, the Sherpas were astonished by the maneuvers, yet another craziness of the obsessed European mountaineers.

My father and Hannes had more than skiing and mountains in common; they shared a similar political outlook. With the election of Hitler as Germany’s chancellor in 1933, discussions between the two men often turned to politics. Hannes and Herman were staunch anti-Nazis, experiencing the ever-threatening tentacles of National Socialism directly and indirectly. First and foremost, each of them mixed easily with the scourge of the Nazis: Jews. Hannes had several professional and personal ties with people of Jewish descent, who – although they may have converted to Christianity – were still classified as Jews according to the Nuremberg Laws. This included a person critical to Hannes’ success: Rudolf Gomperz, the director of tourism for the town of St. Anton, an enduring relationship that contributed to branding Hannes as a “rabid Jew” in Nazi publications. [iv]

Hermann similarly had close associations with Jews. The 1930 Kanchenjunga expedition had been led by Gunter Dyhrenfurth, who according to top Nazi officials belonged “…to the Jewish tribe.” [v] Subsequently my father was viciously attacked by the most powerful man in German mountaineering for having joined an expedition led by a Jew and for not having planted a German flag at the top of Jongsong (instead he flew a Swabian one, appropriate to the region of his birth). In addition, as a member of the prestigious German-Austrian Alpine Club’s Executive Committee, Hermann had fought against Nazi efforts to take over the club and expel Jews from its membership. And worst of all (according to Nazi dictates), he was in love with a woman who was Jewish by background. The same newsletter, Das Schwarze Korps that called Hannes a “Nazi-basher,” was pushing for up to 15 years imprisonment for intimate relations between German of any gender and Jews. [vi] It is no wonder that my father kept the romance secret.

Although my father was not nearly as high profile a figure as Hannes, he was well-known for his first ascents and for starring in a film made about the 1930 Kanchenjunga adventure. Shown in theatres throughout Germany, Austria and Switzerland, Himatschal: Der Thron der Goetter (“Himalayas: The Throne of the Gods”) traced the 1930 expedition in thrilling detail, exposing audiences to extreme Himalayan mountaineering. Released in 1931, it overlapped with the showing of the most popular of several ski films starring Hannes, Der weisse Rausch (“White Ecstasy”), in which he schussed the slopes with the later infamous Leni Riefenstahl. When the two movie stars, both handsome and charming, met shortly afterwards, Hannes joked with my father about his newly acquired fame.

However, other matters were not so cheerful. With growing alarm, Hannes and Herman witnessed increased incidents of Nazi thuggery and persecution rampant in Germany and Austria during the early 1930’s. In St. Anton in 1934, the esteemed international Arlberg-Kandahar race was guarded carefully against disruptive hooligans who shouted Nazi slogans and flashed Hitler salutes. [vii] In both countries, violent street incidents against Jews proliferated and raucous university protests intimidated Jewish students and professors alike. Hermann’s thesis advisor in physics at the University of Stuttgart was married to a Jew; the menacing behavior toward his family motivated my father to sleep on the floor behind the door of his Professor’s home. If need be, Hermann – who slept with his ice axe by his side – was ready to defend him against trouble-makers.

With the 1933 imposition of the notorious 1000 Reichmark tax on any Germans crossing the border into Austria, my father’s ability to see Hannes and certainly to climb in the Austrian Alps ceased. The measure had crippled the Austrian tourist trade [viii] although thanks to Gomperz’s ingenuity and Hannes’ entrepreneurship, the ski school at St. Anton weathered the blow. Having starred in ten skiing films and given ski lessons or demonstrations globally, Hannes continued to attract foreigners to his small village. In 1936 Germany lifted the punitive tax levy, an event celebrated by Germans and Austrians alike, as a sign of the return to friendly relations between the two countries. In retrospect, it was an ominous precursor to the German Anschluss two years later, when Austria fell totally under the domain of the Third Reich and Nazi precepts.

The story of Hannes’ instant imprisonment after the Anschluss by the Nazis is well known, as is his eventual departure to the United States in early 1939. His plight, decried internationally, was initially brought to everyone’s attention by Alice Damrosch Wolfe Kiaer, a wealthy American socialite and serious skier who visited St. Anton for several winters. The daughter of the well-known conductor of the New York Symphony

Orchestra, Alice was part Jewish. Ironically, someone of Jewish extraction again proved to be of key assistance to Hannes.

My father had managed to emigrate six months to America before Hannes, but in his case, it was a “good Nazi” who helped him. Hitler’s personal adjutant had paved the way for Hermann to marry and emigrate. In a rare exception to the Nuremberg Laws, Hermann married the woman who would become my mother in July 1938. Her status as a Mischling (someone with mixed Jewish heritage) is noted in their marriage certificate as is the “special permission” of the Fuehrer.

Once Hannes and his family reached American shores, it did not take long for them to connect with Herman (in deference to his new environs, he had dropped the second “n” from Hermann) and his wife Kate, a widow with three children, whose first husband had been killed by the Nazis during the infamous 1934 purge, the Night of the Long Knives. Herman’s first piece of news to Hannes was that Kate was expecting a baby and asked whether the great skiing icon would agree to be (its ) godfather. On June 25, 1939, Hannes attended my baptism in our backyard in Binghamton, New York. He is listed on the baptismal certificate as Johannes Schneider and he, along with several other European refugees, celebrated my arrival as the “first real American” among them. What made the scene especially poignant was that Hannes’ wife was extremely ill with cancer and Hannes had left her bedside in North Conway to come. In August, Hannes became a widower, left with his two children Herbert, age 19 and Herta, age 18.

Over the next few years, North Conway was often frequented by my parents, my mother’s presence welcomed at the Schneider house for her cooking in addition to her company, especially by Herta. For my father, it was a chance to go skiing with Hannes and the two men enjoyed themselves on the slopes significantly, a welcome respite for Hannes who usually worked ferociously toward making the ski school a resounding success. When Hannes had first come to North Conway, he had asked “Where are the mountains?” Skiing in the eastern United States contrasted sharply with the above tree-line open slopes and formidable peaks of the Alps. But Hannes had applied himself to expanding the ski area tremendously and felt at home, appreciative of the town’s embrace, the support of his sponsors and of living in freedom. He and my father, on their outings, inevitably talked about the war raging in Europe, wondering how and by whom the Nazis could be stopped. When the United States entered the war in 1941, they hoped they knew the answer.

By the end of 1942, gasoline rationing had been instituted in America and trips to North Conway became prohibitive for my parents. The date also marks the beginning of a steady correspondence in German between Hannes and my family, whom he called “meine lieben Hoerlins” (my dear Hoerlins). [ix] The letters cover a variety of topics from the mundane (Hannes asks my parents to send him sausages, that is Wuerste, from their butcher since he could not find good ones in North Conway) to the momentous (the war). In regard to the latter, Hannes’ thoughts document a running chronicle from the viewpoint of an émigré who fled Nazism: the pain of having one’s homeland destroyed, wishing the war would end quickly and fervently hoping for an Allied victory. A sampling of these emotions follows:

“Now the whole world is up in flames and it will take time to put them out. We must be so thankful that we are here, where things are going so well for us, in contrast to our countries of birth.” (February 19, 1942)

“Now they {Germany and Austria} will really feel the war for the first time… the hospitals must be overflowing with the wounded and the half – frozen. Whether peace will come by the end of the year is a big question…” (January 11, 1943)

“If the eyes of German soldiers have not opened by now, then they are certainly even beyond blinded {after the battle of Stalingrad}.” (February 1, 1943)

“Since our last letters, a great deal has changed in Europe and the foundations are beginning to crumble…I hope that the Allies will not let themselves be fooled by the retreat of the Nazism and fascism. One can see that the war is lost… It will still last this year, but winter is on the side of Allies. Hunger, cold, lack of clothing will be consequential. The bombing of cities is certainly awful, one hardly dares to think about it, how many totally innocent people will die. But who started all of this – this question is clear this time.” (August 10, 1943)

“ Of course I have heard nothing from overseas. Can’t this war ever end?-! So much suffering and poverty worldwide and in spite of this, humanity is not rational (sensible). Now I believe there will be another year of war unless something unforeseen happens. Unless a huge attack is launched, Germany will not collapse. Hopefully I am wrong.” (November 23, 1943)

“There’s not much to say about the war situation. One doesn’t know what will transpire over the next weeks.” (March 31, 1944)

“It is so stupid that {the Axis) are not surrendering… German youth are so blinded in their upbringing and know nothing of the world, only blind obedience to orders. I simply cannot understand the attitude of the Germans, they are past being idiotic, don’t you agree?” (October 14, 1944)

“ It is so sad to hear every day what is being destroyed and that people cannot come to their senses.” (December 11, 1944)

During the war, both Hannes and Herman were considered “enemy aliens,” a designation particularly galling to them, given they had left Europe precisely because of Hitler. In my father’s situation, it meant his job as the director of physics at the Ansco Film Company was jeopardized; for Hannes, it meant restricted travel. However, both men were anxious to be of assistance to their adopted country and not coincidentally, prove their loyalty. Summoned several times to Washington, D.C., each contributed to the American war effort. In the case of Hannes, reportedly frustrated because his alien status did not allow him to be a ski troop instructor (as he was in World War I albeit for Austria), he gave expert advice on military ski equipment and mountain warfare. [x] As for my father, described in official correspondence, as a “…mountain climber of some reknown,”[xi] his detailed maps of mountains on the Italian/Austrian border and in the Berchtesgarden region, near the site of Hitler’s “Eagles Nest,” provided valuable information for reconnaissance and/or bombing missions. Both of these so-called “enemy aliens” played a clandestine role in being of service to the United States. Herman definitely agreed with Hannes, who wrote after one of his Washington meetings, “I was pleased that I can be of a little help in order to win the war.”[xii]

When the war in Europe was finally over in May 1945, Hannes and Herman took stock of mutual friends on both sides of the Atlantic. Some had died, others survived, still others were in prisoner-of-war camps. The circles of mountaineering and skiing intersected frequently and the two friends most often saw eye-to-eye regarding the political stripes of their peers. A few of Hannes’ “Buben” (boys) or ski instructors had fought on the Axis side but were not committed Nazis. Others, who had immigranted to America, had enlisted in the American forces, including Hannes’s son, Herbert. The names of additional Tyrolean instructors who had sided with the United States, such as Toni Matt, Otto Lang, Friedl Pfeifer, and Otto Tschohl, became synonymous with the Arlberg technique and the development of skiing in America.

Both Hannes and Herman had similar post-war experiences. As Hannes wrote to my father, “I never knew I had so many friends in Europe. I receive letters from people who I have never seen and everyone is hungry.”[xiii] Hannes, like my family, spent an enormous amount of money and time sending food packages; I remember well helping my father pack teas and coffee, chocolate and other treats. Moreover, hundreds of people inquired about coming to America and seeking employment here. Hannes constantly had to point out how difficult, almost impossible, it was to immigrate, no matter how excellent a ski instructor someone might be. My father, gainfully employed at Ansco, had similar requests from jobless scientists. Of course, no one who wrote to them had ever been a Nazi , or even a Nazi sympathizer, a claim sometimes doubted by Hannes or Herman.

Once the war was over, Hannes was under considerable pressure to return to St. Anton. His house (which served as his home, a guest house and a ski shop) had been safely kept and the townspeople wanted him back, helping return St. Anton to its former days of glory. Hannes was not tempted, perhaps remembering his experience in October 1938. In a rare moment of impulsiveness, Hannes had bolted from essentially being under house arrest in Germany, making a brief trip to St. Anton to see his family. The citizenry avoided him, former friends shunned him and Nazi youth roughed him up. After he had left, his wife and his children suffered several humiliations. [xiv] He was not anxious to repeat the incident. Quoting a German proverb, Hannes succinctly commented to my father, “ A donkey goes on the ice only once.”[xv]

Over a year later in the summer of 1947, Hannes visited St. Anton with his daughter Herta. In a lengthy letter to my family [xvi], he exclaimed, “ We had a royal welcome… When the train arrived, there was music and a few hundred people at the station. I couldn’t believe my eyes. Young and old…accompanied us to our house that was covered with Alpine flowers. I must confess it was a major event.” The next day Hannes was feted by an official welcoming party with 120 liters of South Tyrolean wine and 120 frankfurters. However, the French occupation troops made it difficult to be too joyous, especially when Hannes discovered that a French lieutenant, his wife, child and their maid inhabited his home. Returning to North Conway after having been heroically received in St. Anton, Hannes concluded, “ It was so very nice, to be in the old country again. But we are so very happy to come back here.” [xvii]

For Hannes as well as my parents, America had become home. As Hannes had written in 1941, “I cannot repeat enough, thank God we are in this country” [xviii] They were fully appreciative of American fairness, the opportunities afforded them and the general spirit of tolerance and freedom. Throughout the war years, Hannes was astonished at the level of support for his ski school and that people continued to flock – both during winter and summer ‘seasons’ – to North Conway, despite gas rationing. Having observed the American reliance on cars, he commented in one letter: “I never would have believed that Americans would ever walk there {Cranmore Mountain}.”[xix] After the war, the area became an even more popular and desirable destination.

By 1946, I was seven years old and ready to learn at the feet of the great Skimeister. He had seen little of me since visits between the families were rare during wartime, although he always sent me birthday and Christmas presents. But for several winters in the late 1940’s, I took lessons at his famed ski school. At the end of the day I would diligently show off to my godfather my finest attempts at stem turns, which were alternately critiqued and praised under his watchful eyes. Summer and fall also became a time for my family to head to New Hampshire and enjoy its surrounds. It was in the autumn of 1951 that I had conquered my first mountain, Mount Washington, with Hannes and my father. The following winter was the last time I saw Hannes. In 1953, my family moved to Los Alamos, New Mexico, the infamous “Atomic City,” where my father took a position and studied the effects of high-altitude nuclear explosions. In his Christmas letter to the Hoerlins in 1954, Hannes wrote: “How sad, that we are so far apart and that we seldom will be able to see one another. There’s so much to chat about…” [xx] Indubitably, Hannes was also feeling the absence of Herta, although delighted by her marriage to Franz Fahrner, an Austrian ski instructor, that brought her back to living in St. Anton and running the family store, Sportshaus Hannes Schneider.

When Hannes died suddenly in April 1955, my father lost a dear friend. Their lives, although very different, had several parallels. Both of them loved the mountains and nature, reveling in winter sports and celebrating the beauty of the world. Both had escaped from under the shadow of the swastika that had threatened their lives in Europe, darkened their days in America and profoundly impacted their futures. Both found refuge in a new country, which they loved. Throughout these years, they had an abiding friendship, one that never faltered.

Bettina Hoerlin, PhD, is a retired professor who taught at the University of Pennsylvania and Haverford College. She has held a number of health administrative positions including Health Commissioner of Philadelphia. Her first book, “Steps of Courage: My Parents’ Journey from Nazi Germany to America,” was released in September 2011.

[i] Frank S. Smythe, Climbs and Ski Runs (London: A&C Black Limited, 1929), p. 176

[ii] Hoerlin was credited with first winter ascents of the Aiguille Noire and the Aiguille Blanche de Peuterey (1929)

[iii] F.S. Smythe, The Kangchenjunga Adventure (London: Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1930), p. 293.

[iv] E. John B. Allen, The Culture and Sport of Skiing: From Antiquity to World War II

(University of Massachusetts Press, 2007), p. 397.

[v] Letter from Paul Bauer to the German Sports Minister, Hans von Tscahmmer und Osten, December 10, 1934.

[vi] Saul Friedlander. Nazi Germany and the Jews, volume I: The Years of Persecution, 1933-39 (New York: HarperCollins 1997): p. 122

[vii] E. John B. Allen, ibid., p. 396

[viii] Shofar Archive of the Nizkor Project, Nazi Conspiracy and Aggression, volume 2, chapter XIV, pages 944-45.

[ix] I possess only Hannes’ letters to my father, but the tenor of the correspondence makes clear their mutual feelings about the war.

[x] Gerard Fairlie. Flight without Wings: The Biography of Hannes Schneider (New York: A. S. Barnes and Company, 1957), p. 217.

[xi] Letter from William Honkala, Investigator, U.S. Treasury Department to E.J. Ford, Special Assistant Attorney General, Department of Justice. June 22, 1943.

[xii] Letter from Hannes to Herman Hoerlin, June 9, 1943.

[xiii] Letter from Hannes to the Hoerlins, December 20, 1946.

[xiv] Fairlee, ibid. p. 205-6.

[xv] Letter from Hannes to the Hoerlins, April 25, 1946. “Der Esel geht nur einmal aufs Eis…”

[xvi] Letter from Hannes to the Hoerlins, October 9, 1947

[xvii] Letter from Hannes to the Hoerlins, October 9, 1947

[xviii] Letter from Hannes to the Hoerlins, January 11, 1943.

[xix] Letter from Hannes to the Hoerlins, February 1, 1943.

[xx] Letter from Hannes to the Hoerlins. December 19, 1954