The origins of Cranmore Mountain Resort, dating back 75 years to the New Year’s holidays of 1937, lie in an ancient rivalry between adjacent townships in what is now called the Mount Washington Valley. Stung by the reality that his daughter had to travel to nearby Jackson to find ski instruction and pastures suitable for skiing, Harvey Dow Gibson’s loyalties to the home of his youth, North Conway, were aroused, and he resolved to create a ski area that would put his hometown on the national map of the young sport. One result would be that soon the contention between the local towns would be absorbed into a wider focus on regional promotion under the legend of the Eastern Slope Region. Another, more dramatic outcome would be the rescue of Hannes Schneider and his family from Nazi house arrest on the verge of the Second World War.

There are striking parallels between Harvey Gibson and Hannes Schneider. Both were born to families of humble station in small railroad towns in the mountains that relied on fledgling tourism economies. Both had a personal magnetism and innate dignity that drew people to them and contributed to their ascents. Both rose to almost unbelievable international prominence—even dominance—in their respective spheres of finance and sport. Both their hometowns experienced lasting prosperity thanks to the contributions of these native sons. Each had a connection to an apolitical figure with power in Germany’s Third Reich that would together enable Schneider’s escape from a darkening future in Europe. As the defining historical event of the 20th century drew near in 1939, both were pulled together in a dramatic footnote to world history in which Gibson rescued Schneider from his German detention. The two first met only days before North Conway’s native son brought St. Anton’s leading citizen to the White Mountains of New Hampshire on February 11, 1939. The momentous and welcome result for North Conway and New England skiing would be that Schneider would help Gibson’s resort at Mount Cranmore become for a time the most successful in New England, making it an incubator of growth of the sport in America.

Harvey Dow Gibson was born in North Conway on March 12, 1882, in a house that still stands on the corner of Artists’ Falls Road and North-South Road, now occupied by the GB Carrier Company. He and his older sister Fannie spent their early years in the neighborhood surrounding the long-gone Portland & Ogdensburg railroad station where their father was employed, which was situated at the junction of Depot Road and today’s North-South Road. The P&O had been constructed from Portland Maine up through nearby Crawford Notch by 1875, planned to connect Ogdensburg, New York on the St. Lawrence River with the Atlantic at Portland, to provide a rail route for grain from the Great Lakes states for international export. The rail line never made it further than Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, but its dramatic route through picturesque Crawford Notch ensured substantial passenger traffic.

Gibson’s family had roots in the hotel business in North Conway, a tradition that he would echo in his adulthood as owner of the Kearsarge House and Eastern Slope Inn. His grandfather James M. Gibson, between migrations to the California and Nevada gold fields in the mid nineteenth century, was proprietor of the Washington House, located roughly where Bob and Terry’s Sports Outlet now stands on the White Mountain Highway. His mother, Addie W. Dow, was the niece of the proprietor of the Merrill House in Kearsarge, and grew up waiting on tables in the inn for her uncle.

Gibson’s father, James L. Gibson, found employment as a telegraph operator at the P&O station in North Conway, just a block away from his father’s hotel. Over a matter of years, he became the station agent, and after the rail line became the Maine Central Railroad in 1888, he grew to be a confidante of the executive vice president of the railroad, Payson Tucker. Tucker established a summer home in North Conway named Birchmont, where the Red Jacket Inn now stands, and on his trips to the area came into contact with James Gibson, as messages for Tucker from all over the system came through Gibson’s station. Tucker took an interest in the stationmaster, and helped him establish a sideline lumberyard business next to the station, which still thrives today as a branch of Hancock Lumber. Besides a dynamic executive, Tucker was an alcoholic given to occasional absences when railroad managers could not reach him. At those times, James Gibson was often the only person who could locate him and convince him to return to his executive duties. The diplomatic ability demonstrated by Harvey Gibson’s father in those delicate situations would be echoed in the son’s remarkable rise to the peak of the financial industry in decades to come.

The Birchmont, originally the summer home of Payson Tucker, was later purchased by Gibson for Manufacturers Trust Company as a country retreat for its employees.

Harvey Gibson was educated in the one-room District 14 school in North Conway, on the site of today’s Schoolhouse Motel, then attended Fryeburg Academy in nearby Fryeburg, Maine. His school day began when he and other town boys caught the 5:24 AM train from his hometown to ride the ten miles across the Maine border, and ended when the return trip dropped them off after 6 PM. The point of traveling to Fryeburg Academy was to prepare for a college career, and Gibson at first contemplated attending Dartmouth. After his sister Fannie, older by three years, married Bowdoin graduate Ernest R. Woodbury of Saco, Maine, the glowing reports of his brother-in-law convinced him that Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine was the place for him. Gibson’s connection with the Woodbury clan would be further strengthened in the future, when Gibson’s nephew Wendell D. Woodbury became the overseer of Gibson’s affairs in North Conway.

On graduating from Bowdoin in the class of 1902, Harvey Gibson was hired by the American Express Company, ostensibly as part of a nucleus of college men in a new Financial Department. In actuality the Boston office was not informed of these plans, and Gibson was treated as an office boy and set to sweeping the floors on his first day. Eventually he was promoted to the Financial Department, and while there managed to befriend the chief, who he wrote was regarded as “an intolerant old bull” by all in the office. Through a combination of charm, perseverance, and willingness to learn an arcane bookkeeping system called the Mundle sheet, Gibson converted the curmudgeon into an ally who promoted him. When the Financial Agent position in the Montreal office came open, Gibson was the only Mundle system expert in Boston, and the promotion meant that he had free rein to operate in Canada without direct supervision.

After four years in Montreal, American Express transferred Gibson back to Boston, to London, back to Boston, and finally to New York. Everywhere he went he impressed his coworkers and superiors, and left a trail of goodwill. He had a Yankee shrewdness in dealing with red tape, which he demonstrated once in taking over a disorganized department whose correspondence was in woeful arrears. Gibson bundled packets of unanswered letters and documents and shipped them unread to company offices across the country. On receipt of these seemingly misdirected letters, the remote branches sent them back to Gibson’s office, where they arrived spaced out in time such that Gibson could deal with each overflowing envelope as it arrived. Keeping silent as to his method, Gibson came to be seen as an organizational savant.

While serving as assistant manager of the financial department in New York in 1910, Gibson was tasked by the express company to explore the purchase of a Boston travel company. After Gibson and a colleague arranged to acquire the Raymond-Whitcomb Company, at the last minute American Express dropped their bid, and Gibson and his partner jumped at the opportunity to give their notice and buy it for themselves.

The travel company purchase was Gibson’s first experience with debt, and he was helped through the process by banker Seward Prosser of the Astor Trust Company, whose firm would benefit by the hefty deposits that the travel company would make in his nearby bank. Gibson’s two years in the travel business would represent a minor footnote in his financial career yet important for the positive impression he made on Prosser, a banker with ambition and connections. In 1912, Seward Prosser became president of the Liberty National Bank in New York, and he invited Gibson to leave his travel company and move to Liberty National as assistant to the president. Thus it was that on March 4, 1912, Harvey Dow Gibson, nearly 10 years after his Bowdoin graduation, became a banker and began a truly remarkable rise that would take him to the top ranks of international finance.

Within a year, Gibson was named vice president at Liberty, after he passed through a subtle character assessment arranged by board member Henry P. Davison, who would have a large impact on Gibson’s further career. Gibson was given to understand he would be promoted, but when the board met, Davison asked that the appointment be delayed. Gibson gave no hint of dismay, declaring he had no desire to be vice president unless the entire board was behind him. This was precisely the reaction that Davison was hoping for when he set up his experiment to see how Gibson handled adversity, and within days Gibson had his promotion.

By the end of 1916, again through the intercession of Henry Davison, Gibson was named president of the Liberty National Bank. From that point on, Davison, a senior partner of the influential JP Morgan & Company, assumed a paternal interest in Gibson and the two became close friends. Gibson served as president of Liberty until 1921, when the bank merged with the New York Trust Company, with Gibson leading the combined firm under that name.

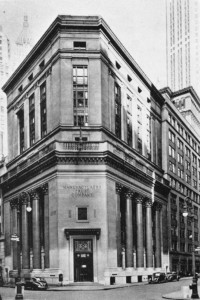

Banking was a precarious profession for some after the Depression took hold in 1929, but Gibson emerged from the banking crisis of 1931 as one of the leading lights of the industry. When the Manufacturer’s Trust Company fell into financial difficulties, the small group of New York’s most stable banks that made up the New York clearing house decided to admit the ailing bank provided a new president and policies were installed. The clearing house committee named Gibson as their choice to lead Manufacturer’s Trust, and within days Gibson formed a group of forty investors and purchased a controlling interest in the bank from Goldman, Sachs. On his first day of work at his new bank Gibson, after having to ask directions to its headquarters, was startled to receive a welcoming visit from J. P. Morgan himself. Gibson was proud to report that no such visit by Morgan had ever been made in Wall Street memory.

For the rest of his life, Gibson would serve as president of Manufacturer’s Trust Company with great distinction. He was peripatetically active in civic life in New York in the period between the world wars, and during the two conflicts he served overseas with the American Red Cross for years at a time. His reputation as a troubleshooter gained him unusual assignments. When $20 million in gold coins was shipped across the Atlantic after the 1914 outbreak of war to fund Americans trapped by the collapse of banking interactions between Germany and Britain, Harvey Gibson was chosen to accompany it. When small banks went out of business and needed to be liquidated, Manufacturer’s Trust could be counted on to do the job well. When the 1940 New York World’s Fair tottered on the brink of insolvency, Gibson was named chairman of the board and paid the creditors and rescued the investors.

From the overall perspective of Gibson’s lifelong accomplishments, his founding of Cranmore may appear as one of the least. Nevertheless, he never lost his love for his native town, and when he was goaded by his daughter Whitney Bourne’s desire to ski in Jackson because there was no place in North Conway, he quickly put together the elements of a brand new ski resort, at a time when the ski resort was a new concept.

“Dear Averell:” wrote Gibson to his friend and fellow magnate W. Averell Harriman, who had just created the ski resort at Sun Valley, Idaho. “If any of your friends want to go skiing, tell them about this little centre Helen and I are developing primarily to create activity in my home town.” Much of the formula that Sun Valley designed was repeated by Gibson in North Conway, and the two carried on some correspondence about their respective resorts. Harriman visited North Conway to take a look at the new Cranmore area, but a rainy weekend precluded any skiing.

Mechanical engineer George Morton of Bartlett was the designer of the unique Skimobile that Gibson financed at Mount Cranmore. Courtesy of the Gibson/Woodbury Charitable Foundation

Mirroring Sun Valley, Cranmore offered expansive ski slopes served by uphill conveyances invented especially for each resort, with the best Austrian ski instructors, coupled with genteel lodging options nearby. Even the major ski races at both areas were similarly named—the Harriman races at Sun Valley and the Gibson Cup events at Cranmore both celebrated the respective founders. As the winter of 1938 progressed, most of the pieces were in place at Cranmore for a first-class Harvey Gibson operation; the only element missing was the world’s most renowned ski teacher.

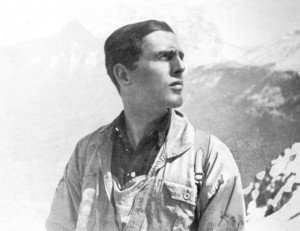

Just prior to the running of the 1938 Arlberg-Kandahar race in St. Anton, Austria, German troops entered Austria in the bloodless occupation/annexation known as the Anschluss. Hannes Schneider, until then the town’s leading citizen by virtue of the robust prosperity that his internationally famous ski school had created, found himself the target of native Austrian Nazi party followers who had previously been powerless to sway opinion to their cause given the steadfast opposition of Schneider. Politically Schneider was a follower of Chancellor Englebert Dollfuss (1982-1934), who was assassinated by Nazis, and his successor as Chancellor, Kurt von Schuschnigg (1897-1977), who was forced to resign in the Anschluss. A degree of antagonism to Schneider’s anti-Nazi sentiments had been in evidence since 1933, personified by former instructor Karl Moser, an early Nazi with ambitions to lead the ski school who had resigned when visits by German tourists died off in the wake of the imposition of a tax of 1000 Reichsmarks on entry to Austria. There were several prominent attacks on Schneider in the press, in particular for his refusal to cut ties to Rudolph Gomperz, the tourism director of St. Anton who was in part responsible for the installation of the Galzig cable car, and who was born a self-described “non-arian”.

In the immediate wake of the Anschluss, Schneider was arrested and sent to the Landeck jail, though the policeman who took him in was apologetic to Hannes to such an extent that he was fired days later. Karl Moser was made mayor of St. Anton, and two days after the Anschluss organized a celebratory parade through St. Anton in which all were forced to march. Friedl Pfeiffer, one of Schneider’s top instructors watching from the sidelines with a broken leg, witnessed American racer Betty Woolsey marching alongside in her own counter-demonstration, shouting “Ski Heil” and displaying “a decidedly different hand salute to the Nazis” than the now-mandatory Nazi upraised arm. Franz Gabl, another of Schneider’s teachers, noted that Germans flooded into town so that business was brisk, and that without Hannes’ stern discipline “there were so many women—and many were eager for romance—and the moral standard was considerably lowered”.

The worldwide outcry that followed Schneider’s imprisonment in Landeck was triggered by American Alice Wolfe and Englishman Arnold Lunn, both good friends of Schneider with wide acquaintance in international skiing circles. Wolfe went to Landeck, she remembered in 1955, to “bribe the jailer to let me visit Hannes, more to have him comfort me than anything else.”

Karl Rösen, who was active in German ski organizations, was instrumental in protecting Schneider after his arrest.

Perhaps through Wolfe, or some other skiing connection, Dr. Karl Rösen, a German attorney from Garmisch-Partenkirchen, was enlisted in Schneider’s case, and after 25 days in Landeck, Schneider was transferred to Garmisch under Rösen’s jurisdiction.

The house where Hannes Schneider was held under house arrest in Garmisch, seen in 2012. Photo by Heide Allen.

He had been president of the Bavarian Ski Association in the 1920s, and was an honorary member of the Kandahar Ski Club of Mürren, the partner club with the Arlberg that put on the Arlberg-Kandahar races. Rösen had been a court-appointed lawyer to Hitler at the time of the 1924 Beer Hall Putsch, though his client conducted his own defense and Rösen’s name does not appear in historical accounts. Nevertheless, he evidently maintained enough influence in Berlin to shield Schneider from the personal vendettas of the Austrian Nazis, and transfer him to German territory where the Nazi party not only had nothing against Schneider, but were aware that he was a bit of a public relations dilemma for them. Acting as a friend and advocate but not as attorney for Schneider, Rösen appears to have ghost-written a well-referenced reply to the criticisms of Schneider addressed to Heinrich Himmler, and held in abeyance any potential reprisals until Gibson’s unexpected lifeline appeared from overseas.

As part of his creation of Mount Cranmore, Harvey Gibson had purchased the ski school in Jackson started by Carroll Reed, which had been his original motivation to bringing a ski resort to North Conway. Benno Rybizka, the lead instructor in Jackson, had been sent by Schneider in the winter of 1937 in response to Carroll Reed’s plan, and by 1938 was working with Gibson in North Conway. He undoubtedly alerted Gibson to Schneider’s situation, and the desirability of having Schneider at Cranmore. As early as March, 1938, Gibson drew up a contract between the Eastern Slope Ski School and Schneider for the directorship of the school, and gave the London representative of the Manufacturer’s Trust Company, Herbert W. Auburn, the task of negotiating with the Nazis for clearance for Schneider to emigrate to the US. Auburn, an assistant vice president in the Foreign Department of Gibson’s bank, reportedly had direct discussions with Himmler.

Gibson also happened to be the chairman of the American Committee of Short Term Creditors of Germany, a consortium of banks that held non-performing German debt. This committee had much to discuss with their German negotiating partner, Reichsbank president Hjalmar Horace Greeley Schacht (1877-1970). Gibson and Schacht were acquaintances, perhaps from the early days of World War I when Gibson was a go-between for English and German banks before America’s entry in the war. Schacht was not a Nazi party member, and experienced a gradual diminution of his power until he was dismissed in 1943 and placed in a series of concentration camps in 1944 for resistance activity. Interestingly, at the end of the war, he was in the same transport of prominent political prisoners as Kurt von Schuschnigg from Dachau to the Tyrol. In any event, the net result of the negotiations, which went unrecorded and were subject to a non-disclosure agreement, between Gibson and Schacht, Rösen and Himmler, and Auburn and his contacts, was that Hannes Schneider was allowed to emigrate to the US with his wife Ludwina, daughter Herta, and son Herbert. Probably not coincidentally, American banks continued to extend commercial credit to Germany under a “standstill agreement”; on March 31, Germany’s credit lines with international banks totaled $81 million.

With the February 11, 1939 arrival of the Schneider family in North Conway, with Harvey Gibson at their side as they walked through an arch of ski poles formed by youth of the Eastern Slope Ski School, North Conway and Cranmore began an emergence as one of the most successful ski resorts in the US, a status that would continue well into the 1960s.

Hannes and Ludwina Schneider were welcomed to North Conway by Harvey Gibson on February 11, 1939. Benno Rybizka is on the left. Herbert Schneider is glimpsed behind Hannes wearing a white cap, and Herta Schneider is seen between Mrs. Schneider and Mr. Gibson.

“Without Mr. Gibson’s help we could not have gotten the necessary passports and US entry papers”, Schneider wrote to Otto Lang. “For this I shall be eternally grateful to him….When one has gone through what I had to endure, one cannot help but to be grateful and happy to be a human being again and to be offered the opportunity to earn a living”.

The window in which Gibson and Schacht reached an accord on Hannes Schneider’s release did not remain open for long. Before the next ski season, as construction proceeded on the upper stretch of the Skimobile that Schneider insisted was needed to reach the summit of Cranmore, and on the day that Harvey Dow Gibson assumed leadership of the New York World’s Fair, September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland, and shattering conflict would soon engulf the world.

Harvey Gibson spent the World War II years overseas with the Red Cross, and was welcomed home by a laudatory editorial in the New York Times. He remained president of Manufacturer’s Trust Company until his death in 1950. Many North Conway organizations and individuals benefited form the charitable instincts of Gibson and his wife Helen.

Hannes Schneider remained a North Conway resident and director of the Hannes Schneider Ski School until his death in 1955. His wife Ludwina died about six months after their arrival in North Conway.

Herta Schneider returned to St. Anton about 1949 and married Franz Fahrner; together they ran the Fahrnerhof guest house. Herta died in 2001.

Benno Rybizka left Cranmore soon after Hannes’ arrival, and taught at Mittersill and Mont Tremblant. He returned to St. Anton after the war, where he died in 1992.

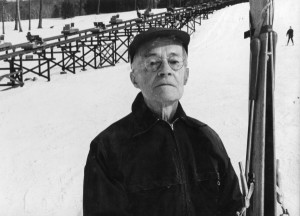

Herbert Schneider took over the Hannes Schneider Ski School on his father’s death, and purchased Cranmore Mountain from the heirs of Harvey Gibson. He owned and operated Cranmore until 1984, and was an active force in the Professional Ski Instructors of America, several ski resort trade associations, and the town that offered his family refuge in 1939.